Insomnia and Substance Addiction

Sleep problems and substance addiction go hand in hand more often than most people realize. If you’re struggling with addiction, in recovery, or supporting someone who is, understanding this connection can make a real difference in your healing journey.

Drugs and alcohol don’t just affect you while you’re using them—they mess with your sleep patterns in ways that can last for months or even years. This creates a vicious cycle where poor sleep makes cravings stronger and relapse more likely, while substance use keeps destroying your natural sleep rhythms.

We’ll explore how different substances disrupt your sleep and why insomnia becomes such a common problem for people with addiction. You’ll learn about the brain science behind this connection and discover practical treatment options that address both sleep issues and substance use together. Most importantly, you’ll understand why getting quality sleep isn’t just about feeling rested—it’s a crucial part of staying sober and rebuilding your life.

How Substances Disrupt Your Sleep Patterns and Daily Functioning

Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Problems Caused by Drugs and Alcohol

Drugs of abuse and alcohol significantly interfere with the fundamental processes of falling asleep and staying asleep throughout the night. These substances create substantial barriers to sleep initiation, making it increasingly difficult for users to transition from wakefulness to sleep naturally. The disruption extends beyond just falling asleep, as maintaining continuous, restorative sleep becomes progressively more challenging with substance use.

Alcohol consumption initially appears to help with sleep onset, particularly in individuals with insomnia, as it can normalize slow wave sleep patterns. However, this apparent benefit is short-lived and deceptive. Tolerance to alcohol’s sleep-inducing effects develops rapidly after just six nights of use, forcing users to consume increasingly larger amounts to achieve the same sleep-promoting effects. This tolerance development creates a dangerous cycle where individuals progressively increase their alcohol intake in pursuit of sleep relief.

Stimulants like cocaine present a different pattern of sleep disruption, causing delayed sleep onset and significant sleep fragmentation during periods of abstinence. The stimulating effects of these substances can keep users awake for extended periods, fundamentally altering their natural sleep-wake rhythms and creating a state of hyperarousal that persists even when the acute effects of the drug have worn off.

Disruption of Natural Sleep Stages from NREM to REM Sleep

Substances of abuse systematically disrupt the natural progression through sleep stages, fundamentally altering the cycling from non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. This disruption affects the restorative quality of sleep and interferes with critical neurobiological processes that occur during different sleep phases.

REM sleep suppression is particularly common during active substance use, followed by dramatic REM rebound effects during withdrawal periods. This pattern is especially pronounced in alcohol-dependent individuals, where disturbed REM sleep patterns persist long after achieving abstinence. Polysomnographic studies reveal that alcohol-dependent individuals experience shortened REM latency and elevated REM percentage, abnormalities that can predict higher relapse risk.

Cannabis acutely affects sleep architecture by decreasing sleep latency, increasing total sleep time, and enhancing slow-wave sleep while simultaneously decreasing REM sleep. However, with chronic use, tolerance develops to these sleep-enhancing effects. During abstinence from cannabis, users experience poor sleep quality and unusual dreams, reflecting the disrupted REM sleep patterns that have been suppressed during active use.

The disruption of sleep stages has profound implications beyond just sleep quality. These alterations affect memory consolidation processes and the brain’s ability to process and integrate daily experiences, potentially interfering with learning and cognitive function essential for recovery from addiction.

Next-Day Impairment Including Daytime Sleepiness and Reduced Alertness

The sleep disruptions caused by substance use inevitably translate into significant next-day functional impairments that extend far beyond simple tiredness. Users consistently experience increased daytime sleepiness and markedly reduced alertness, creating a cascade of problems that affect daily functioning and quality of life.

Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) results consistently show elevated latencies in individuals with substance-related sleep problems, indicating a state of hypervigilance or hyperarousal that paradoxically coexists with excessive sleepiness. This seemingly contradictory state reflects the complex neurobiological disruptions caused by substance use, where the brain remains in a heightened state of arousal even while struggling with sleep deprivation.

The daytime impairment significantly affects cognitive function in addicted individuals. Sleep is crucial for memory consolidation and the process of extinction learning, which is essential for forming non-reinforced drug associations needed for recovery. When sleep dysfunction interferes with these processes, it may actually impede the learning mechanisms necessary for successful addiction treatment and long-term recovery.

Chronic sleep loss and insufficient sleep can produce such severe daytime sleepiness that individuals turn to stimulant use as a form of self-medication. This creates additional layers of substance dependence, as people use caffeine, nicotine, or stronger stimulants to combat the sleepiness caused by their primary substance use, establishing complex patterns of polysubstance use.

Sleep Disturbances During Active Use and Withdrawal Periods

Sleep disturbances manifest differently during active substance use compared to withdrawal periods, creating distinct challenges that users must navigate throughout their addiction trajectory. During active use, substances directly interfere with sleep architecture and quality, while withdrawal periods often bring their own unique set of sleep-related problems.

During withdrawal from various substances, sleep disruption becomes particularly severe and takes on characteristics specific to the substance involved. Stimulant withdrawal, for example, is characterized by increased sleepiness and sleep fragmentation, which may paradoxically promote further stimulant use as individuals attempt to reverse these uncomfortable effects through self-medication.

Opioid withdrawal presents especially challenging sleep disturbances, with the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system becoming robustly activated during withdrawal, contributing to the hyperarousal and insomnia that characterize opioid withdrawal syndrome. This neurobiological activation creates a state where sleep becomes virtually impossible, driving individuals back to substance use to find relief from the overwhelming insomnia and associated withdrawal symptoms.

The persistence of sleep abnormalities during protracted abstinence represents one of the most challenging aspects of recovery. These ongoing sleep problems can last for months or even years after achieving sobriety, creating a significant risk factor for relapse. The chronic nature of these sleep disturbances helps explain why sleep problems are such strong predictors of relapse risk across various substance use disorders, making sleep restoration a critical component of comprehensive addiction treatment approaches.

Understanding Insomnia as the Primary Sleep Disorder in Addiction

Clinical Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Insomnia in Substance Users

The evaluation of insomnia symptoms in substance users requires comprehensive clinical assessment that extends beyond standard diagnostic protocols. Healthcare professionals utilize a multi-faceted approach combining direct psychiatric evaluation through daily clinical interviews with objective data collection methods. A critical component involves implementing sleep logs maintained by night-shift nursing staff, who document patient sleep patterns hourly between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m., providing essential complementary information to support accurate diagnosis.

Clinical criteria establish four distinct insomnia classifications that frequently manifest in substance users:

-

Sleep-onset insomnia: Characterized by failure to fall asleep within the first 30 minutes of attempting sleep

-

Sleep-maintenance insomnia: Defined by two or more nocturnal awakenings per night

-

Early awakening: Occurs when patients wake at least one hour before their usual time

-

Poor sleep quality: Encompasses cases where patients experience daytime consequences including sleepiness, fatigue, irritability, nervousness, decreased concentration, muscle tension, and headaches, even without meeting other specific criteria

Research demonstrates that insomnia symptoms affect 66.5% of patients during active detoxification processes, with an overwhelming 84.3% reporting previous insomnia experiences. Sleep-maintenance insomnia emerges as the predominant type, followed sequentially by early morning awakening, sleep-onset insomnia, and poor nocturnal sleep quality.

Classification Differences Between DSM-5 and ICSD3 Guidelines

The DSM-5 framework approaches substance-related sleep disturbances through its comprehensive substance-induced disorders classification system. Within this structure, substance-induced sleep disorders represent a distinct diagnostic category encompassing insomnia and other sleep problems directly caused by drug, alcohol, or medication use. The DSM-5 recognizes that these sleep disturbances must cause significant distress and functional impairment in daily life to warrant diagnosis.

The DSM-5’s substance-induced sleep disorder classification requires establishing a clear temporal relationship between substance use and sleep disruption onset. This diagnostic approach emphasizes that sleep symptoms must not be better explained by intoxication or withdrawal effects alone, distinguishing between acute substance effects and persistent sleep disorders that develop during or persist beyond the acute phase of substance use.

Hyperarousal and Elevated Alertness Patterns in Affected Individuals

Specific demographic and clinical patterns emerge when examining hyperarousal states in substance users with insomnia. Research reveals that insomnia symptoms occur more frequently in women and older individuals, suggesting gender and age-related vulnerabilities to sleep disruption during substance use and recovery.

Particularly significant patterns emerge among different substance user populations. Patients with heroin use disorders demonstrate significantly higher rates of insomnia symptoms compared to those with other substance use disorders. Polysubstance users exhibit markedly elevated insomnia prevalence, indicating that multiple substance use creates compounded sleep disruption effects.

Comorbid conditions substantially influence hyperarousal patterns. Patients with concurrent medical conditions show significantly increased insomnia symptoms, while specific psychiatric comorbidities create distinct risk profiles. Anxiety disorders, ADHD, cluster B personality disorders, and histories of previous detoxification admissions correlate with heightened insomnia occurrence.

Multivariate analysis identifies independent risk factors for insomnia during detoxification:

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 3.43 | 2.01-5.86 | p = 0.0001 |

| Polysubstance use | 2.85 | 1.79-4.54 | p = 0.0001 |

| Anxiety disorder comorbidity | 2.09 | 1.06-4.12 | p = 0.03 |

| Prior detoxification admission | 1.22 | 1.07-1.38 | p = 0.002 |

These patterns indicate that hyperarousal states in substance users result from complex interactions between substance effects, individual vulnerability factors, and concurrent medical and psychiatric conditions.

The Critical Role of Sleep Disturbances in Addiction Cycles

How Sleep Problems Contribute to Initial Substance Use Development

Sleep disturbances frequently serve as a pathway to initial substance experimentation and use. While the reference material primarily focuses on relapse patterns, it’s clear that sleep problems are universal withdrawal symptoms across all substance types, suggesting they play a foundational role in the addiction cycle from the very beginning. Chronic heavy substance use produces negative effects on sleep regardless of the specific substance used, indicating that individuals may initially turn to substances as a misguided attempt to self-medicate existing sleep difficulties.

The prevalence of sleep problems in substance use populations is remarkably high, with baseline studies showing 79% of individuals in recovery experiencing significant sleep disturbances. This overwhelming prevalence suggests that sleep issues may precede and contribute to substance use initiation, creating a vulnerable population that seeks relief through psychoactive substances.

Sleep Issues as Maintenance Factors in Ongoing Addiction

Once substance use begins, sleep disturbances become powerful maintenance factors that perpetuate addictive behaviors. The relationship becomes cyclical – drinking predicts poor sleep among people with alcohol use disorder over extended periods, with the effects of drinking on sleep being mediated by depression levels. This creates a self-reinforcing pattern where individuals continue using substances to manage sleep problems that are actually being worsened by the substance use itself.

Sleep problems contribute to higher relapse rates through multiple interconnected mechanisms including increased stress, elevated stress reactivity, chronic negative affect, persistent pain, and intensified drug craving. The impairment of cognition and judgment caused by sleep deprivation further compounds these issues, making it increasingly difficult for individuals to make rational decisions about substance use.

Sleep disturbances in various substance use disorders consistently correlate with negative treatment outcomes, demonstrating their role as maintenance factors across different types of addiction. For cocaine users, while sleep may improve with abstinence, the early abstinence period is particularly vulnerable as sleep impairment during this time increases relapse risk significantly.

Sleep Abnormalities as Predictors of Relapse Risk

The predictive power of sleep disturbances for relapse has been extensively documented across multiple substances. The largest body of evidence involves alcohol dependence, where both subjective and objective sleep measures at baseline have consistently predicted subsequent relapse. A comprehensive 2003 review cited 12 publications demonstrating this critical relationship between sleep disturbance and relapse.

Specific sleep abnormalities have emerged as particularly strong predictors. Increased sleep latency and its subjective correlate – trouble falling asleep – along with significantly more rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or “REM pressure,” are replicated predictors of alcoholic relapse. In one notable study, 60% of alcohol patients with insomnia relapsed within five months compared to only 30% without insomnia.

For cocaine and amphetamines, vivid, unpleasant dreams during withdrawal are associated with more severe disorder features and increased relapse risk. REM sleep pressure has been independently documented as associated with relapse in these populations. Cannabis users experiencing sleep disturbances during abstinence show high relapse rates, with poor sleep prior to quit attempts predicting relapse within just two days.

Nicotine dependence shows similar patterns, with nighttime awakening measured by withdrawal scales being negatively associated with abstinence after six months. A history of smoking during sleep was linked to earlier relapse within four weeks of the quit date.

Chronic Nature of Sleep Disturbances in Recovery

Sleep problems demonstrate remarkable persistence throughout the recovery process, often lasting far longer than other withdrawal symptoms. Among patients who maintained abstinence for one full year, 33.9% still experienced moderate sleep problems while 18.6% continued to have severe sleep difficulties. This persistence makes sleep disturbances one of the most enduring challenges in long-term recovery.

The chronic nature of these sleep issues creates ongoing vulnerability. Patients with alcohol use disorder who experienced insomnia after 5 months of abstinence were at greater risk for relapse at 14 months, demonstrating how sleep problems can threaten recovery stability even after extended periods of sobriety. Persistent sleep problems are consistently associated with psychological distress and are experienced as a major challenge in maintaining drug-free status.

Participants frequently report difficulty falling asleep, waking up multiple times throughout the night, and experiencing vivid dreams or nightmares related to past drug use. These sleep problems tend to fluctuate over time, with some individuals experiencing periods of better sleep while others face persistent issues lasting months or years into recovery.

The establishment of regular sleep practices has emerged as an important marker of successful recovery, yet most individuals in recovery have little experience with effective treatments for sleep problems. This treatment gap represents a significant challenge, as sleep problems are often overlooked in clinical settings despite posing major obstacles to maintaining sobriety.

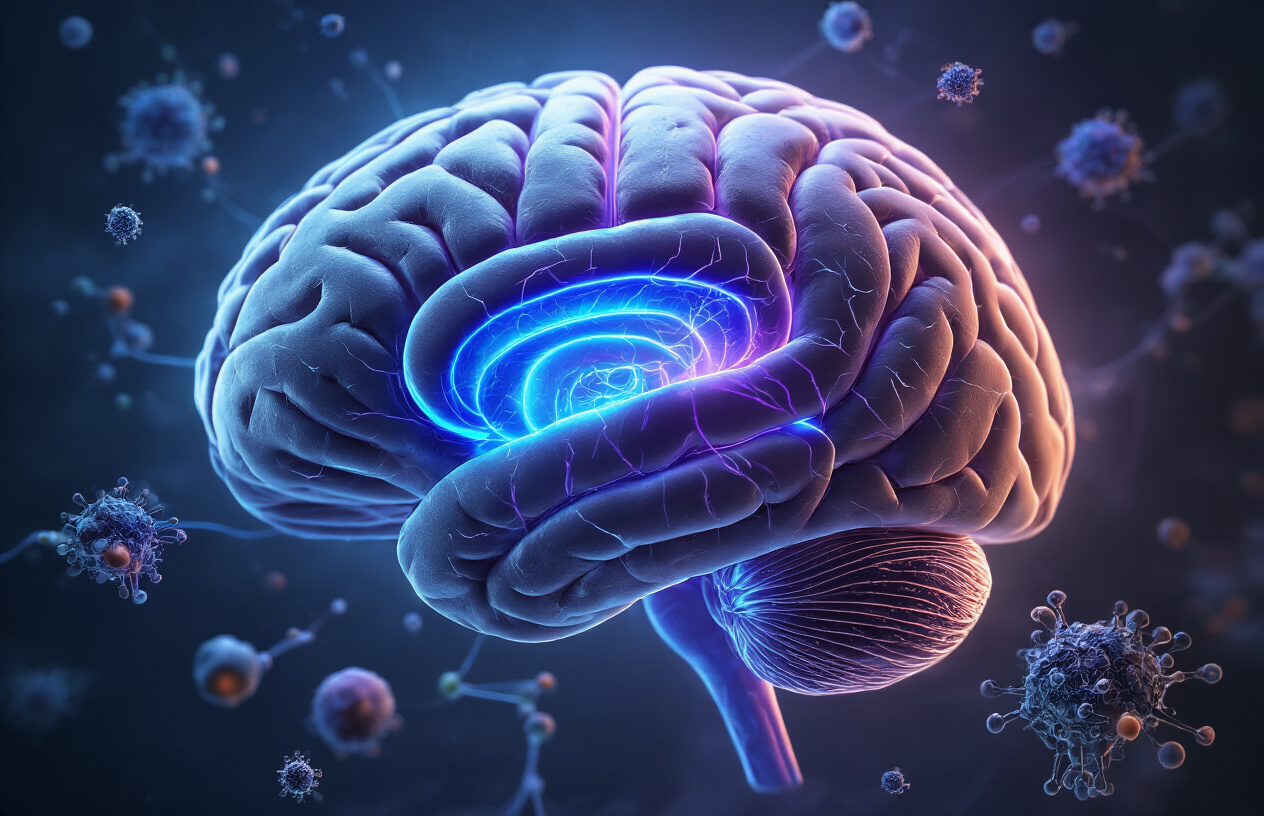

Neurobiological Connections Between Sleep and Addiction

Shared Hyperarousal Pathways in Both Conditions

The neurobiological foundations of sleep disorders and addiction reveal striking similarities in their underlying pathways. Research demonstrates that limbic neural circuits responsible for individual differences in incentive motivation significantly overlap with those involved in sleep-wake regulation. This overlap creates a complex interplay where sleep disturbances and substance use disorders share common neurobiological mechanisms, particularly in hyperarousal states that characterize both conditions.

Individual differences in drug-craving behaviors are closely linked to variations in sleep patterns and neural circuit activation. The sign/goal-tracker model of Pavlovian conditioned approach in rodents illustrates how only certain individuals develop key behavioral traits associated with addiction, including impulsivity and poor attentional control. This selectivity suggests that shared hyperarousal pathways may be more active or sensitive in vulnerable populations.

HPA Axis and Stress Hormone Involvement

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis plays a crucial role in connecting sleep disturbances with addiction vulnerability through stress hormone regulation. While the reference material doesn’t provide specific details about HPA axis mechanisms, the connection between stress systems and reward circuitry becomes evident when examining how sleep disruption affects motivational systems. The limbic circuits that govern both sleep-wake cycles and reward-seeking behaviors are intricately connected to stress response pathways.

Brain Circuit Activation in Stress and Reward Systems

Animal studies have extensively examined the impact of sleep on reward circuitry, revealing how altered sleep patterns affect brain circuit activation. The limbic neural networks that control incentive motivation and sleep regulation demonstrate significant overlap, creating a neurobiological foundation for understanding why sleep problems increase addiction risk. These shared circuits explain how disrupted sleep can amplify reward-seeking behaviors and increase vulnerability to substance use.

Increased Vulnerability to Drug Abuse Through Sleep Disruption

Sleep disturbances create increased risk for substance use disorders and relapse, though this vulnerability affects only select individuals. The individual differences in how sleep deprivation contributes to addiction highlight the importance of understanding why some people are more susceptible to these neurobiological connections. Preclinical models demonstrate that consideration of individual differences would improve our understanding of how sleep interacts with motivational systems, providing insight into the mechanisms underlying selective vulnerability to addiction through sleep disruption.

Treatment Approaches for Sleep Issues in Substance Users

Medication Options Including Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists

Benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics, which include both benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines, represent a significant concern in substance use disorder populations. These medications should be strongly discouraged due to dependency, tolerance, and mortality-related issues. Benzodiazepines bind non-selectively with Bz1, Bz2, and Bz3 receptors, where Bz1 produces hypnotic and amnestic effects, while Bz2 and Bz3 provide antiseizure and muscle relaxing properties.

Non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists, including Z-drugs (Zaleplon, Zolpidem, Zopiclone), bind selectively with Bz1 GABA receptors only and act as allosteric modulators. However, research from a large United Kingdom primary care cohort revealed that anxiolytics and hypnotics drugs were associated with significant mortality over a seven-year period, even after adjusting for potential confounders. The fatal toxicity of Zopiclone was not significantly different from benzodiazepines as a group when adjusted for usage.

In acute intoxication and withdrawal phases, medications for insomnia should only be prescribed on an as-needed basis. The primary recommendation during these phases should focus on abstaining from substances that induce sleep disturbances rather than relying on potentially addictive sleep medications.

Sedative Antidepressants and Alternative Pharmacological Solutions

FDA-approved alternatives to benzodiazepine receptor agonists include selective melatonin receptor agonist (Ramelteon 8mg), selective histamine receptor antagonist (low-dose Doxepin 3mg-6mg), and dual orexin/hypocretin receptor antagonist (Suvorexant 10mg-20mg). These medications should be preferred over benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics in substance users.

Off-label use of various psychotropic medications is common in clinical practice for treating insomnia in substance users, particularly when comorbid psychiatric issues are present. Non-FDA approved medications commonly used include:

-

Trazodone (25-200mg at bedtime)

-

Quetiapine (dosage varies based on clinical needs)

-

Mirtazapine (7.5mg-15mg)

-

Hydroxyzine (25-100mg)

-

Gabapentin (100-900mg)

The use of these psychotropic medications for insomnia can be justified, particularly when comorbid psychiatric issues exist, since untreated insomnia can exacerbate most psychiatric problems. These alternatives provide safer options for substance users while addressing both sleep disturbances and underlying mental health conditions.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Benefits and Limitations

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) represents the gold standard for non-pharmacological treatment and should be utilized as an initial intervention when appropriate conditions permit. CBT-I is as effective as prescription medication for short-term treatment of insomnia, with beneficial effects lasting well beyond the termination of active treatment, unlike medications.

Core Components of CBT-I:

Sleep Restriction: This technique improves sleep continuity by limiting time spent in bed to match reported sleep time. It increases sleep drive via controlled sleep deprivation and is effective for both sleep onset and maintenance problems. The goal is achieving 85% sleep efficiency, calculated as time asleep divided by time in bed.

Stimulus Control: Considered one of the most effective behavioral treatments, this approach changes the association between the bed and wakefulness. Instructions include maintaining fixed morning rise times seven days a week, using the bed only for sleep and sex, leaving the bedroom if awake for more than 20 minutes, and avoiding daytime napping.

Sleep Hygiene: This involves avoiding caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol, eating light bedtime snacks, sleeping in quiet, dark rooms with comfortable temperatures, limiting napping, and exercising in the afternoon or early evening.

Cognitive Therapy: This component challenges dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, such as “I must sleep 8 hours” or “I should never wake up at night,” requiring cognitive restructuring to address automatic negative beliefs.

However, CBT-I has limitations in substance use populations. While limited data supports its success in substance users, its utilization as a first-line treatment option can be difficult due to the nature of addiction disease. The typical CBT-I treatment plan consists of 4-5 sessions followed by booster sessions, which may require sustained engagement that some individuals in early recovery may struggle to maintain.

Specialized Medications for Specific Substances Like Acamprosate for Alcohol

While the reference content does not provide specific information about acamprosate or other substance-specific medications for sleep disorders, it emphasizes that treatment approaches must consider the complex relationship between different substances and sleep disturbances. According to ICSD-3, substances that induce sleep disorders include alcohol, opioids, cannabis, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, cocaine, stimulants, hallucinogens, nicotine, and inhalants.

The treatment approach varies depending on the specific substance involved. For alcohol use disorder, the relationship between insomnia and relapse risk is particularly concerning. Patients with baseline insomnia are more likely to report frequent alcohol use for sleep (55% vs. 28% in those without insomnia) and show much higher relapse rates to any alcohol use (60% vs. 30% in those without baseline insomnia).

The integrated treatment approach must address both the sleep disorder and the specific substance use pattern. Treatment of insomnia should be incorporated into the recovery plan for substance use populations, as untreated insomnia significantly increases the chance of relapse. This comprehensive approach recognizes that different substances affect sleep architecture differently and may require tailored interventions beyond standard sleep medications.

The emphasis remains on cognitive and behavioral therapies as the preferred initial treatment approach, with or without medication, while avoiding benzodiazepine receptor agonist medications whenever possible to prevent additional dependency issues in an already vulnerable population.

The complex relationship between insomnia and substance addiction reveals a troubling cycle where sleep disturbances both contribute to and result from substance use disorders. Substances disrupt critical sleep stages, impair next-day functioning, and create chronic sleep abnormalities that can persist for years, significantly increasing relapse risk. The neurobiological pathways shared between insomnia and addiction—particularly those involving hyperarousal and stress response systems—demonstrate why sleep problems are so prevalent among individuals struggling with substance use.

Understanding these connections is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies. While various approaches exist, from benzodiazepine receptor agonists to cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, the limited impact on preventing relapse highlights the need for more comprehensive interventions. If you’re experiencing both sleep difficulties and substance use issues, seeking professional help that addresses both conditions simultaneously may be essential for breaking the cycle and achieving lasting recovery. The evidence clearly shows that treating sleep disturbances isn’t just about getting better rest—it’s a vital component of addiction recovery that deserves serious attention.